Unicode - born for the Web

Project report for Tufts COMP150 Internet-scale Distributed Systems(Spring 2016). I tried to explain the prevalence of UTF-8 on the Web, from the perspective of history and technology.

Posted with minor changes in wording and format.

Introduction

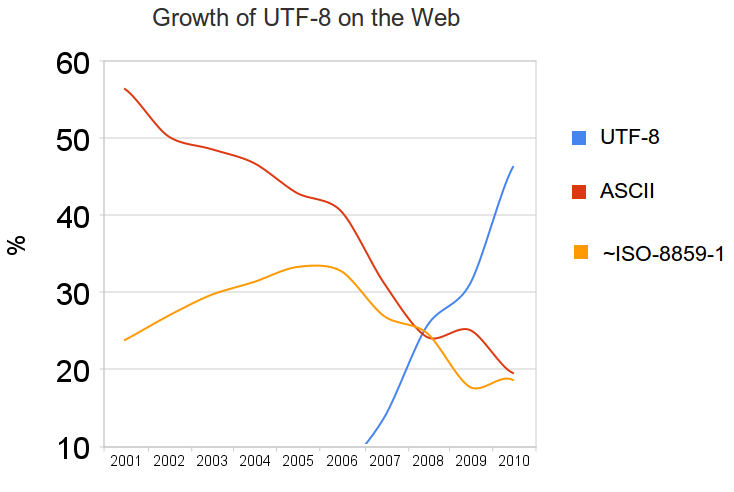

UTF-8, a family member of the Unicode Standard, is the dominant character encoding on the Web1. According to a survey2, UTF-8 is used by 86.9% of all the websites as of May 20163. This did not happen overnight. In Jan 2010, only half websites were using UTF-8, and nearly a third were using ISO-8859-1, an encoding system generally intended for Western European languages. If we tracked back further, we would see a totally different landscape of character encoding schemes. In 2001, ASCII was the main encoding of text on the Web (55%+), followed by ISO-8859-1(20%+). UTF-8 did not get any important visibility4.

Figure -1: Growth of UTF-8 on the Web

Figure -1: Growth of UTF-8 on the Web

Nonetheless, UTF-8 has won the game of representing contents on the Web.In 2007, W3C recommended that

”Everyone developing content, whether content authors or programmers, should use the UTF-8 character encoding, unless there are very special reasons for using something else.” 5

Furthermore, in 2013, W3C asked people to

”choose UTF-8 for all content and consider converting any content in legacy encodings to UTF-8.”6

The report focuses on the encoding problem for web content. The encoding for other web components, such as URIs and CSS, is not discussed.

The Problem7

What is a character encoding

On the Web, all words and sentences in a text are created from characters which are grouped into a character set. The characters are stored in the computers in the form of bytes. A character encoding is a set of mappings between the bytes in the computer and the characters in the character set. Without the correct keys, the decoding can be in a mess, and the information represented will be lost. ASCII, ISO-8859-1, and UTF-8 are examples of character encodings.

Why encoding is important for the Web

Character encoding has been an important issue since the Web was born. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the Web, realized that incompatible character encoding schemes, among many other incompatible problems, made any attempt to transfer information between dislike systems a daunting and generally impractical task8. In an age of globalization where internet got more popular, encoding was in the central of cross-platform and cross-cultural communication. The IETF Policy on Character Sets and Languages published in 1998 gave a short but convincing description of the encoding problem9:

“The Internet is international”

and

“With the international Internet follows an absolute requirement to interchange data in a multiplicity of languages, which in turn utilize a bewildering number of characters.”

Why encoding is difficult for the Web

The difficulties mainly stem from the diversity of languages, particularly the writing systems. Also, the languages are evolving and new characters, such as emojis, are created every day. The classic 8-bit, single-byte ASCII encoding is sufficient for encoding English and many European languages. However, many non-European languages, such as Chinese, Japanese, and Korean languages, include much more characters that cannot be represented in a single-byte encoding scheme. Therefore, the multibyte character set is required. Based on the Metcalfe’s Law, the Web would be much smaller without an appropriate and uniform encoding. The Web would be divided by the languages, such as Web for people using Western European languages or the Web for people using Asian languages, etc. As such, World Wide Web requires worldwide encoding. We may say “uniform encoding leads to network effects”. Also, people tend to underestimate the difficulties of developing a uniform encoding. For example, in “RFC 373 Arbitrary Character Sets10“, John McCarthy11 proposed an implementation of arbitrary character sets:

“Each character has a unique number, 17 bits should be enough even to include Chinese.”

17 bits means that the size of codespace is 131,072. However, there are 120,737 code points in UTF-8 Version 8 launched in 201512. 17 bits might not enough. Making people all over the world to accept a uniform encoding is not easy. People living in the U.S. may wonder why would we bother to switch to a new encoding.

The Evolution

Before the Web was born

In early days, before the invention of the internet and the Web, computers rarely communicated with one another. When inter-computer communication became possible, the need for encoding standards became apparent. Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC) was one of the choices of encoding back then, due largely to the popularity of IBM machines, ASCII was another option.

The birth of the Web

When he first proposed the Web for European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in 198913, Tim chose ASCII. However, The drawback of ASCII is that for many European languages, the accented characters and diacritical marks could not be included due to space limitation14. Early ASCII only had 7-bits or 128 code points. Then, there came the ISO 8859 series (and ISO Latin-1), which is a superset of ASCII and was an attempt to provide alternatives for languages other than English. In 1993, in a draft on Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), Tim wrote 15

” The base character set (the SGML BASESET) for HTML is ISO Latin-1.This is the set referred to by any numeric character references .The actual character set used in the representation of an HTML document may be ISO Latin 1, or its 7-bit subset which is ASCII.”

The real problem is that many writing systems do not use Latin letters. Some similar encodings were developed for non-latin speaking languages, e.g. CJK. The number of characters in a typical encoding is increasing, which brought the multibyte encodings. However, it is difficult to identify characters within a byte stream, and the adaption of the program from a single byte to multibyte requires huge work, and different multibyte encodings require different adaptations16. At the early days of the Web, the needs for international communication over computers is low, and the problem was not so bad.

The booming of the Web and the chaos of encodings

As the fast growth of the Web in the 1990s, there emerged several encodings for different languages. The complexity and diversity of the characters encoding can best be reflected in W3C’s HTML 4.01 Specification released in 1999, especially in chapter 5.2.1 “Choosing an encoding”17:

“Commonly used character encodings on the Web include ISO-8859-1 (also referred to as “Latin-1”; usable for most Western European languages), ISO-8859-5 (which supports Cyrillic), SHIFT_JIS (a Japanese encoding), EUC-JP (another Japanese encoding), and UTF-8 (an encoding of ISO 10646 using a different number of bytes for different characters). Names for character encodings are case-insensitive, so that for example “SHIFT_JIS”, “Shift_JIS”, and “shift_jis” are equivalent. “

The specification did not mandate which character encodings a user agent must support. However, the incompatibility of different encodings had created a great chaos in international communication over the Web.

The rise of the Unicode family: born for the Web

The needs for combining all languages using standard encoding became urgent as the growth of the Web. Specifically, people may want to write documents that mix text from two or more languages for international communication over the Web. Also, the search results pages could include results from different locales and therefore in multiple languages. There were at least two separate projects dedicated to creating a uniform encoding standard: ISO/IEC 10646 by ISO and the Unicode Standard by the Unicode Consortium. In 1991, the ISO Working Group responsible for ISO/IEC 10646 (JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2) and the Unicode Consortium decided to create one universal standard for coding multilingual text18. Unicode was first proposed in 1988 intending to create a character repertoire covering “all the scripts of the world”. When making the proposal, Joseph Becker realized that

”The problem with ASCII is simply that the people of the world need to be able to communicate and compute in their own native languages, not just in English. Text processing systems designed for the 1990’s and the 21st century must accommodate Latin-based alphabets for European languages such as French, German, and Spanish; and also major non-Latin alphabets such as Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, and Russian; and also “exotic” scripts of growing importance such as Hindi and Thai; not to mention the thousands of ideographic characters used in writing Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. What is needed is a new international/multilingual text encoding standard that is as workable and reliable as ASCII, but that covers all the scripts of the world”.19

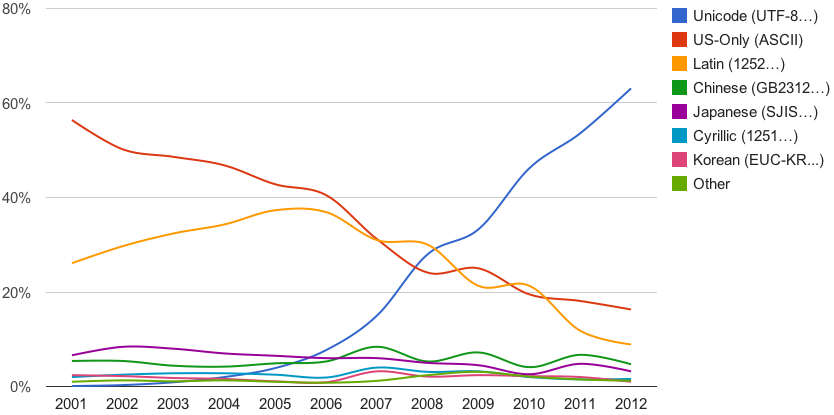

Unicode was first published in 1991, which is exactly the year people outside of CERN were invited to join the Web community20. To some extent, Unicode and the Web mutually reinforce the growth of each other. From 2001 to 2012, the percentage of the web pages in Google’s index using Unicode had increased from 0 to more than 60%.

Figure 2: The rise of the Unicode(UTF-8)21

Figure 2: The rise of the Unicode(UTF-8)21

In W3C’s 2015 recommendation,

“The utf-8 encoding is the most appropriate encoding for interchange of Unicode, the universal coded character set. Therefore for new protocols and formats, as well as existing formats deployed in new contexts, this specification requires (and defines) the utf-8 encoding.”

The Winner

Why Unicode

The principles that the Unicode Standard try to follow make Unicode encodings great candidates for the characters encoding on the Web.

- Simplicity Unicode is so popular first lies with its simplicity, and simplicity supports scalability. There are at least three principles making Unicode Standard a simple(doesn’t mean easy) solution to a complicated problem.

- Universality The Unicode Standard encodes a single repertoire that covers all the characters for worldwide use, not only modern writing system but also historical texts and emojis. In addition, the code points have been expanding to include new characters. The universality makes the Unicode Standard meet the needs for a diverse and globally distributed internet users. Unicode supports multiple languages and can display pages in a mixture of those languages. The server-side doesn’t need to individually determine the character encoding for each page served or each form submitted.

- Efficiency All character codes have the same status as any other character code, or all codes are equally accessible. Unlike EBCDIC or ISO 202222, there are no escape characters or shift states in the Unicode character encoding model, which makes randomly accessing and searching inside streams of characters efficient23(#fn:uniform-efficiency “See footnote”).

- Unification The Unicode Standard avoids duplicate encoding of characters. This would make punctuation marks, symbols, and diacritics represented by unique code points. In addition, Chinese/Japanese/Korean languages share many characters for historical reasons, and common letters will be given one code each.

- Stability Since web contents tend to be public and living for many years, it’s very important that the encodings are stable. Unicode adopts following policies to meet the stability requirement24:

- Once code points are assigned to characters, they cannot be changed, nor can characters be removed. Then users can be guaranteed that text data retains the same meaning.

- Unicode character names are unique and never changed so that they can be used as identifiers in different versions of the standard.

- Convertibility On the Web, before the UTF-8 dominates the Web, there were many encoding standards co-existing, which causes messes and pain for users. The Unicode Standard solves the problem by incorporating a number of different base standards. Generally, a single code point in another standard corresponds to a single code point in the Unicode Standards. Sometimes, a single code point in another standard corresponds to a sequence of code points in the Unicode Standard, or vice versa. The existence of a mapping between the Unicode Standard and base standards is guaranteed. The convertibility lowers the barriers to transfer to the Unicode Standard, which make a great contribution to the scalability of the standard.

Why UTF-8

Unicode itself is not an encoding. Instead, it is a standard that can be implemented in different encodings, such as UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32, etc. The numbers in the encodings imply the code unit or a single unit within each encoding form25. E.g. for UTF-8 the fewest bytes per character is 1 bytes, while for UTF-16, it is 2 bytes (16 bits). UTF-8 was designed and implemented by Rob Pike and Ken Thompson of the Plan 9 operating system group at Bell Labs. The reason they did this was that they had used the original UTF from ISO 10646 to make Plan 9 support 16-bit characters, but they “hated it26” because it poorly supported historical file systems and existing Unix implementations. An encoded character takes between 1 and 4 bytes. The letter x indicates bits available for encoding bits of the character number27.

Char. number range | UTF-8 octet sequence

(hexadecimal) | (binary) ———————–+——————————-

0000 0000 - 0000 007F | 0xxxxxxx

0000 0080 - 0000 07FF | 110xxxxx 10xxxxxx

0000 0800 - 0000 FFFF | 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

0001 0000 - 0010 FFFF | 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx

There are several properties make UTF-8 an attractive solution for the encoding on the Web.

- Self-synchronizing Character boundaries are preserved by well-defined bit patterns. For example, an octet starting with 0 means it is a code for a one-byte character, while an octet starting with 1110xxxx means it is for a three-bytes character. If bytes are lost due to error or corruption, one can easily locate the beginning of the next valid character. The missing of such property from IBM’s proposal of improving the original UTF was one reason that Rob and Ken decided to write their own encoding28.

- Very good Interoperability and backward compatibility All ASCII characters in UTF-8 use the same bytes as an ASCII encoding, therefore ASCII text is valid UTF-8.

- Endianess independent E.g. UTF-16 has two flavors with two different byte orders, so there has to be some way to assist in recognizing the byte order.

- Efficient use of space For an ASCII character, UTF-8 uses 1 byte, but UTF-16 needs 2 bytes and UTF-32 4 bytes. Even for CJK contents, sometimes UTF-8 could get huge size win over UTF-16 for storing the DOM text due to the fact in DOM file CKJ characters are embedded in tags which use latin characters29.

One problem

To the end users, there is an illusion that if they use the correct tag in the header, e.g, the web content should be displayed correctly. However, this is not true. The simple reason is that UTF-8(and other Unicode encodings) is the encoding for characters, not for glyphs, for the sake of separation of concern. In other words, getting encoding and decoding correctly done doesn’t mean the users can see the result. In order to show some specific characters, fonts that support such characters must be available from the system. For example, there are 12000+ codepoints in Unicode, but the Arial font only supports 3988 of them. People need to download new fonts to support desired Unicode characters. For example, the Unicode of the rain symbol  is U+26C6, but people usually only see a blank rectangle ⛆ from the browsers since there is no font for the symbol living in the system.

is U+26C6, but people usually only see a blank rectangle ⛆ from the browsers since there is no font for the symbol living in the system.

Summary

The World Wide Web requires a uniform encoding for the contents so that the Web works in all languages, scripts, and cultures. UTF-8 takes the responsibility and is the most frequently used character encoding on the Web. UTF-8 inherits the simplicity, stability, and convertibility from the Unicode Standard. Furthermore, UTF-8 wins the competition to other Unicode encodings for the ability of self-synchronizing, backward compatibility, and space efficiency. However, without appropriate system support(e.g. fonts), the power of the Unicode character encoding could be compromised.

Further Reading

- UTF-8: Bits, Bytes, and Benefits. Russ Cox, 2010

- Hello World or Καλημέρα κόσμε or こんにちは 世界 - Bell Labs. Rob Pike and Ken Thompson, 1993

Notes

-

If you are curious the characters encoding of a web page, just check the page source. It’s highly possible that you will see something like . ↩

-

“Historical yearly trends in the usage of character … - W3Techs.” 2010. May 2, 2016 http://w3techs.com/technologies/history_overview/character_encoding/ms/y ↩

-

Another survey indicates a lower but still reamarkable penetration rate, see http://trends.builtwith.com/encoding/UTF-8 ↩

-

“UTF-8 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.” 2011. May 2, 2016 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UTF-8 ↩

-

“Introducing Character Sets and Encodings - W3C.” 2007. May 2, 2016 http://www.w3.org/International/getting-started/characters.en ↩

-

“Choosing & applying a character encoding - W3C.” 2013. May 2, 2016 https://www.w3.org/International/questions/qa-choosing-encodings ↩

-

“Character encodings: Essential concepts - W3C.” 2013. May 2, 2016 https://www.w3.org/International/articles/definitions-characters/. The document provides a great introduction on the most important concepts of character encodings, including Unicode, Character sets, code points, coded character sets, and encodings, etc. ↩

-

“The World Wide Web: Past, Present and Future - W3C.” 2008. May 5, 2016 http://www.w3.org/People/Berners-Lee/9610-IEEE-Computer-v1.html ↩

-

“RFC 2277 - IETF Policy on Character Sets and Languages - IETF.” 2010. May 2, 2016 https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc2277/ ↩

-

“RFC 373 - Datatracker - IETF.” 1972. May 2, 2016 https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/rfc373/ ↩

-

McCarthy was one of the founders of the discipline of artificial intelligence. “John McCarthy (computer scientist) - Wikipedia, the free …” 2011. May 3, 2016 ↩

-

“BabelStone: How many Unicode characters are there ?.” 2005. May 3, 2016 http://babelstone.blogspot.com/2005/11/how-many-Unicode-characters-are-there.html ↩

-

“Information Management: A Proposal - W3C.” 2015. May 3, 2016 https://www.w3.org/History/1989/proposal.html ↩

-

Early ASCII only had 7-bits, or 128 code points. ↩

-

“Tutorial: Character Encoding and Unicode.” 2010. May 3, 2016 http://www.w3.org/International/talks/0505-Unicode-intro/ ↩

-

“HTML Document Representation.” 2015. May 3, 2016 https://www.w3.org/TR/html4/charset.html ↩

-

“FAQ - Unicode and ISO 10646 - Unicode Consortium.” 2005. May 3, 2016 http://Unicode.org/faq/Unicode_iso.html ↩

-

Becker, JD. “Unicode 88 - Unicode Consortium.” 1988. http://Unicode.org/history/Unicode88.pdf ↩

-

“History of the Web – World Wide Web Foundation.” 2014. May 5, 2016 http://webfoundation.org/about/vision/history-of-the-web/ ↩

-

“Official Google Blog: Unicode over 60 percent of the web.” 2015. May 5, 2016 https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2012/02/unicode-over-60-percent-of-web.html ↩

-

“Stateful encodings - IBM.” May 4, 2016 https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/SSLTBW_2.1.0/com.ibm.zos.v2r1.cunu100/iea3un_Stateful_encodings.htm ↩

-

Reminded by Prof. Noah Mendelsohn: Encodings like UTF-8 can be complex to search and compare, at least in comparison to fixed width encodings like ASCII. ↩ ↩

-

“Unicode Character Encoding Stability Policies - Unicode Consortium.” 2007. May 4, 2016 http://Unicode.org/policies/stability_policy.html ↩

-

“Relationship of Code Points and Code Units - MSDN - Microsoft.” 2015. May 4, 2016 https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms225454(v=vs.80).aspx ↩

-

“Rob Pike’s UTF-8 history.” 2011. May 4, 2016 https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~mgk25/ucs/utf-8-history.txt ↩

-

Yergeau, F. “RFC 3629 - UTF-8, a transformation format of ISO 10646 - IETF Tools.” 2003. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3629 ↩

-

“Rob Pike’s UTF-8 history.” 2011. May 6, 2016 https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~mgk25/ucs/utf-8-history.txt ↩

-

“416411 – Analyze mozilla’s usage of strings, dynamically … - Bugzilla.” 2008. May 5, 2016 https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=416411 ↩